From Birmingham to Bridgton – A Trailblazer’s Journey

December 22, 2020

Benjamin Davis ’63 was born and raised in Birmingham, Alabama. With both of his parents being educators, the  importance of learning and expanding one’s intellect was a foundational philosophy for Ben and his three siblings. Ben’s childhood was spent in a south still dominated by Jim Crow laws. In fact, from preschool through his sophomore year of high school, Ben could only attend racially segregated schools. Living under the “separate but equal” doctrine of that time, Ben’s parents believed that he and his siblings deserved a better educational experience. “The black schools certainly weren’t equal,” Ben shares. “From the buildings to the books, it was all second class. The results of this were evident in both the test results and attendance. The educational opportunities for black students back then were extremely limited.” His parents discovered the American Friends Service Committee, a program run by the Quakers to provide educational placement for students from underserved communities. Ben embraced the idea of heading north for school, and at age thirteen, found himself attending high school in New Jersey, spending two years there before graduating at fifteen.

importance of learning and expanding one’s intellect was a foundational philosophy for Ben and his three siblings. Ben’s childhood was spent in a south still dominated by Jim Crow laws. In fact, from preschool through his sophomore year of high school, Ben could only attend racially segregated schools. Living under the “separate but equal” doctrine of that time, Ben’s parents believed that he and his siblings deserved a better educational experience. “The black schools certainly weren’t equal,” Ben shares. “From the buildings to the books, it was all second class. The results of this were evident in both the test results and attendance. The educational opportunities for black students back then were extremely limited.” His parents discovered the American Friends Service Committee, a program run by the Quakers to provide educational placement for students from underserved communities. Ben embraced the idea of heading north for school, and at age thirteen, found himself attending high school in New Jersey, spending two years there before graduating at fifteen.

Upon his graduation, Ben’s school counselor suggested that a postgraduate program may be appropriate for him given his young age. Ben and his family decided on Bridgton Academy, liking what they heard about the postgraduate aspects of the program at that time. Leaving by train from Birmingham in the summer of 1961, the then fifteen-year-old made his way as far north as he had ever ventured—to the rural outpost of North Bridgton, Maine.

“I got to Bridgton and my first impression was that it was a beautiful place, but isolated,” reflects Ben. At that time, Ben was the only person of color in the entire Bridgton Academy community. While he may not have been aware of this, Ben was, in fact, one of the first black students to ever attend Bridgton. He wasn’t a total stranger to this feeling; in New Jersey he had also attended a predominately white school; however, it was a significant shift from his childhood in Alabama. “In Bi rmingham, we lived in a neighborhood that became known as ‘Dynamite Hill’,” Ben recalls. “Whenever a black family moved into this mainly white area, their house would get bombed. Also, the laws required that not only schools, but all public facilities be segregated. All of this was in place to make us feel inferior to whites. Learning became the tool to instill confidence that this falsehood would never be true and that you have every right to achieve your dreams.”

rmingham, we lived in a neighborhood that became known as ‘Dynamite Hill’,” Ben recalls. “Whenever a black family moved into this mainly white area, their house would get bombed. Also, the laws required that not only schools, but all public facilities be segregated. All of this was in place to make us feel inferior to whites. Learning became the tool to instill confidence that this falsehood would never be true and that you have every right to achieve your dreams.”

With this mindset and the support of his family, Ben jumped into life at Bridgton. A musician who played in the school band in his earlier years, Ben was surprised to find that there was no music program at the Academy, so he decided to go out for the sports teams. “I tried to get involved with as many activities as possible at the Academy. Although I was small in stature, I wasn’t afraid or tentative. Everyone was friendly and I don’t recall ever having to feel on guard. I doubt if many of my classmates had ever been around a black guy before, so I guess it was all new to all of us.”

When asked if it ever entered his mind that he was laying the groundwork for a more diverse Bridgton of the future, Ben shares that he was mainly just focused on his work and what he needed to do at the Academy. “I didn’t think of it at the time, of me being a pioneer for other African Americans. I think if I did, I would have worked with my teachers to include more in the curriculum regarding the contributions of African Americans in literature and the history of our country, studying writers such as James Baldwin or Langston Hughes, or Civil Rights leaders such as Rosa Parks and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. My blackness, at Bridgton, became an issue only when my classmates began to discuss racial issues in general. It was never directed towards me, nor was it anything close to the hatred and bigotry I experienced in Birmingham.”

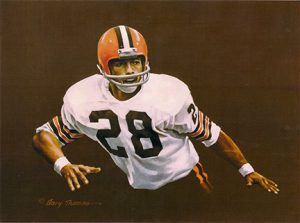

While his family and community were engaged in historic social action at home, Ben remained busy with life at Bridgton, finding his way onto the gridiron for the first time after trying out for the Academy’s football team. His initial motivation for making the team was simply to get off campus and be able to see a bit of the world outside of North Bridgton. Little did he know that this first venture into football would turn into a successful ten-year career in the National Football League. “At Bridgton, they didn’t cut anyone,” Ben remembers. “And, while I didn’t play much, I did at least get to travel!” Ben remembers talking to Coach Bob Walker at the end of the season about the possibility of playing football at Defiance College, a small school in northwestern Ohio. Coach Walker told him that if he worked hard, he had no doubt that Ben would be a starter by his senior year—advice that Ben took to heart and followed with great success.

As life progressed for Ben, he proudly made his way into the National Football League (NFL), drafted by the Cleveland Brow ns after graduating from Defiance. As his own career unfolded, social changes continued to sweep through the United States. This included a meteoric rise to fame of one of Ben’s sisters, Angela Davis.

ns after graduating from Defiance. As his own career unfolded, social changes continued to sweep through the United States. This included a meteoric rise to fame of one of Ben’s sisters, Angela Davis.

“In the late 1960s, Angela moved to San Diego to complete her doctoral degree in philosophy. She also became involved in the Black Power movement, the protests against the war in Vietnam, the fight for prisoner’s rights, womens’ rights, and anyone who was suffering from oppression. In 1970, she became the victim when the state of California charged her with three capital offenses all punishable by death. She was innocent of the charges and later found not guilty. During her incarceration, our family did whatever we could to support Angela. This included raising money for her legal defense and marching and protesting for both her rights and for those of all political prisoners.”

“In the meantime, I was playing in the NFL, trying to extend my career after a season-ending injury. My wife and I started the Free Angela committee in Cleveland and attended her hearings and trial during the off season. As far as I knew, my teammates were supportive. If they weren’t, they didn’t say anything. After games, I would get notes in my locker from players on opposing teams, wanting to know if they could help with Angela’s cause in any way. At the same time, I got plenty of threatening letters and some booing from the crowd. One coach attempted to “fire up” his team by telling them ‘We’ve got to beat those guys (Browns); they’ve got a communist playing the right corner.’ I learned to deal with all of those things—it was part of the process, and eventually, it all turned out well. Today, my sister Angela is an icon. A scholar and activist who has spent the last fifty years working for social justice for people throughout the world.”

Davis reflects on the political action taking place today, in many cases involving the voices of professional athletes. “What greater platform to have when addressing the challenges of our society than that of the professional athlete,” Ben shares. “Racism, police brutality, the criminal justice system…How ironic is it that the very same position Colin Kaepernick took to protest police brutality was the same position used by the Minneapolis police to kill George Floyd?”

Being a child of the Civil Rights Movement, Davis has many thoughts on the social issues related to racial equality taking place in our country today. And even though he has seen many changes during his lifetime, there is still so much road to travel in the work to end systematic oppression in our country. “It’s been a lot of space and time [since the 1960s], but not a lot of real changes,” Ben remarks. “A local minister here in Cleveland was recently appointed as foreman of the grand jury. After his tenure, he remarked that today’s justice system reminded him of apartheid, the oppressive system of institutaional racial segration that existed in South Africa years ago. The administrators of the criminal justice (judge and jury) were all white, whereas everyone being tried were people of color.”

“The biggest problem we have now is that we have what looks like what might be a fully integrated society, but the institutions that run the society are still exhibiting racism. There are a lot of things that need to be dealt with, and ultimately changed. We need to dismantle the face of racism that still exists in our institutions, not just talk about diversity and inclusion. We need to find a way to work together—to be together. This is the path to a better world for all of us.”

Benjamin Davis ’63 attended Bridgton Academy from 1961-1963. In 2004, Mr. Davis was inducted into the Bridgton Academy Hall of Fame for his professional work and life achievements.